Ancestry® Family History

Oklahoma Land Rush

As the United States expanded westward in the 19th century, the government sought ways to open land to would-be settlers. For example, President Abraham Lincoln signed the Homestead Act in 1862 (during the Civil War), which gave land to U.S. citizens, those who intended to become citizens, and those who had not taken up arms against the Union. "Homesteaders" could lay claim to up to 160 acres by paying a small registration fee. These "public lands," which had been acquired through treaties with Native nations, coercement, or forcible removals, are the ancestral homelands of hundreds of Native American tribal nations.

Toward the end of the 19th century, the federal government looked to expand further the amount of land available for settlement. The focus this time was on the Oklahoma and Indian Territories. Between 1889 and 1895, the United States gave away millions of Native-owned acres in those areas to non-Native people who wanted to settle there.

In a series of chaotic land runs (or land rushes), tens of thousands of would-be settlers traveled from around the country to claim a piece of these newly opened territories and start a new life. These land rushes paved the way for Oklahoma to become a U.S. state in 1907.

What Led To the Opening of Oklahoma Territory?

Through the passage of the federal Indian Removal Act of 1830, many Native nations in the U.S. South–like the Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, Creek, and Seminole–were forcibly pushed by the U.S. Army to reservations west of the Mississippi River into what was known as "Indian Territory." But less than 60 years later, the government eyed those lands as well as other lands secured through treaty as targets for additional primarily white settlement. New legislation, in the form of the Dawes Act, was passed in order to make that happen.

Through the passage of the federal Indian Removal Act of 1830, many Native nations in the U.S. South–like the Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, Creek, and Seminole–were forcibly pushed by the U.S. Army to reservations west of the Mississippi River into what was known as "Indian Territory." But less than 60 years later, the government eyed those lands as well as other lands secured through treaty as targets for additional primarily white settlement. New legislation, in the form of the Dawes Act, was passed in order to make that happen.

This additional "opening" of land meant further negotiating with, coercing, or forcibly removing Native Americans from their ancestral tribal lands. It also meant removing Indigenous people from the reservations to which they had voluntarily removed to or had been forced to move to during the "Trail of Tears."

The Dawes Act Divided Native American Land

In 1887, Congress passed the Dawes Act, which split reservations into smaller allotments. Unlike the parcels given out under the Homestead Act, the Dawes Act divided land that Native Americans legally controlled under federal law; the U.S. didn't own it. Even so, the government considered any plots left over—from allotments given to Native people and Freedmen, those formerly enslaved by the Five Tribes and their descendants—to be "surplus" and sold them to non-Native settlers. Through this system, Native Americans lost about 90 million acres of land, an area about twice as large as the state of Oklahoma.

Other actions under the Dawes Act included conducting a census that classified Native people and Freedmen by "blood quantum" (i.e., their supposed percentage of "Indian blood"), and by grouping them into redefined family units. The government typically allotted 160 acres to the head of each newly defined household and 80 acres to unmarried adults. Those who accepted, or were forced to accept, title to the land were then made U.S. citizens.

Congress believed that if Native family units owned and farmed plots of land, they could more easily assimilate into white society. Thus, the Dawes Act disrupted not only Native practices of land stewardship, but also traditional social systems of kinship and household organization.

The U.S. Government Bought More Native American Land for Settlement

By the late 1880s, the United States occupied much of the Northern Plains and Texas and began eyeing what was known as Indian Territory, which included what is now the state of Oklahoma. Mainly white would-be settlers began—and continued—to pressure the government to open up even more lands for settlement in Indian Territory, as improvements in agricultural techniques made the area more appealing for farming. But this area was home, or had become a home, to a number of Native nations, including the Comanche, Kiowa, Choctaw, Cherokee, Apache, Quapaw, and Chickasaw. Although certain tribal nations were able to bypass the Dawes Act through strategic legal action, the U.S. forced other nations, like the Creek and Seminole, to sell their land.

In March 1889, as part of an appropriations bill, Congress authorized opening 1.9 million acres of Indian Territory to settlers under the Homestead Act. This set the stage for the first Oklahoma land rush. President Benjamin Harrison announced that the territory would be open for settlement at noon on April 22. Anyone who moved in earlier would be prohibited from acquiring land.

In March 1889, as part of an appropriations bill, Congress authorized opening 1.9 million acres of Indian Territory to settlers under the Homestead Act. This set the stage for the first Oklahoma land rush. President Benjamin Harrison announced that the territory would be open for settlement at noon on April 22. Anyone who moved in earlier would be prohibited from acquiring land.

How Could People Claim Land in the Oklahoma Territory?

Would-be settlers had to follow rules established under the Homestead Act in order to claim land in the Oklahoma Territory—now called "Unassigned Lands." First, the government surveyed the land before making it available for settlement. Then, any citizen over 21—including formerly enslaved people (which encompassed Freedmen) and single women—could apply for a 160-acre plot. (Those who intended to become citizens were also eligible.) In order to apply, an aspiring settler would go to the local land office and pay about $10 to make a temporary claim. Next, they had to start living on the lot within six months. If they stayed for five years and nominally improved the property, they got a deed of title. Amendments to the Homestead Act allowed settlers to bypass the five-year residency requirement if they paid $1.25/acre and lived on the claim for six months. Union Army veterans could also deduct their time served from the residency requirements. Others purchased land from speculators or railroad companies who sold off the excess land granted to them under the Pacific Railroad Act (1862).

Not everyone stayed long enough to get the land permanently. Conditions were hard. Water was often scarce and there were few trees with which to build homes. Storms and insects destroyed crops, and there was little natural vegetation for livestock to graze on.

Despite the challenges, the Homestead Act offered a remarkable opportunity and appealed to a wide range of Americans. Poor farmers thought they could make a better life for their families if only they had land to cultivate. Speculators and corporations hoped to turn a profit. Professionals angled for land near brand-new towns. Tradesmen and laborers followed, knowing there would be plenty of work as the population grew. So, when land became available in Oklahoma, people rushed to claim it. These opportunities, however, came at a high cost to Native Americans and Freedmen already in the area.

What Happened in the Oklahoma Land Run of 1889?

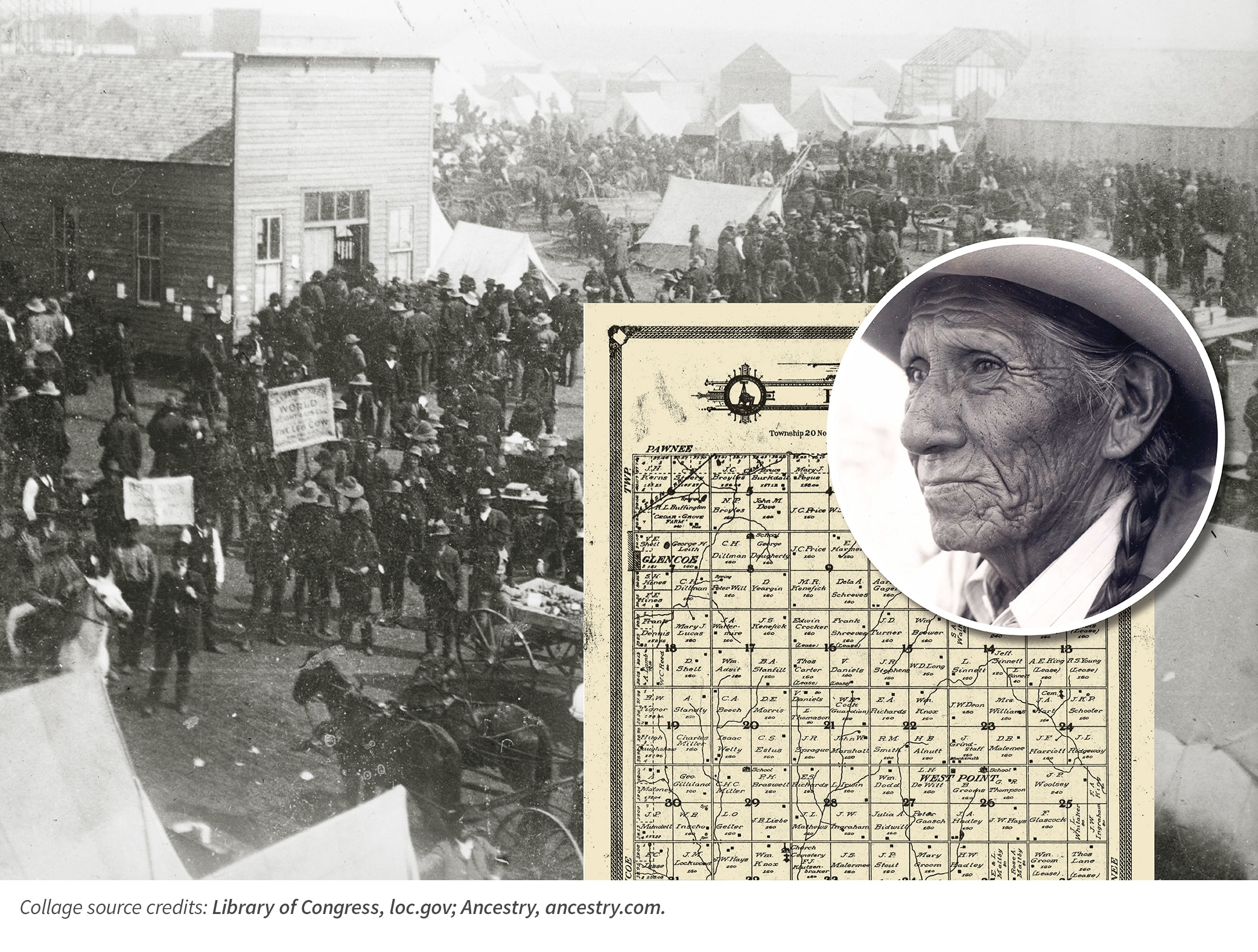

In the spring of 1889, settlers, known as "Boomers," moved toward Oklahoma, often with wagons and livestock in tow, and set up camps in nearby Kansas. Fifteen crowded trains idled in Arkansas City, Kansas, until they could steam forward. On April 22, as many as 100,000 people gathered at the Oklahoma border. At high noon, bugles sounded, cannons boomed, rifles fired, and land-hungry settlers surged into the territory from many directions.

"Sooners" Got in Ahead of Time

While most people waited at the border, some land-seekers entered the territory early, joining settlers who had already been squatting on or leasing land that belonged to Native American tribal nations. Although it violated tribal treaties, the U.S. allowed government and Santa Fe railroad workers to reside beyond the border. Others simply snuck across and hid until April 22. These groups, nicknamed "Sooners," took advantage of the head start and laid claim to the best parcels of Native American land. One newspaper reported that people concealed themselves in the bushes and, when the bugle sounded, they "seemed to rise right up out of the ground."

New Settlers Quickly Claimed the Territory

By the end of the day on April 22, the newest settlers had claimed every available lot. They planted stakes in the ground, laid down a few logs for a cabin, or started digging a well, then headed to the local land office. The towns of Oklahoma City and Guthrie—primarily white settlements—sprang up overnight. Few government officers and troops monitored the land rush, and conflicts inevitably arose about who had the rightful claim to land. Boomer settlers later brought Sooners to court for illegally acquiring plots.

But Boomers and Sooners weren’t the first non-Natives to settle in the area. Years earlier many Blacks had settled in the area. All-Black towns like Marshalltown, Arkansas Colored, and Tullahassee, among others, were already in Indian Territory before 1880. Many of the towns were established by Freedmen. And during the land rushes, dozens of additional all-Black towns were created, as Freedmen and other Blacks sought to create their own communities in these newly opened areas.

How Many Land Rushes Were There in Oklahoma?

Oklahoma had a total of five land rushes, plus one land lottery and one auction. Each followed the seizure of more Native American reservation land. On September 22, 1891, settlers again rushed at noon to claim their piece of the 900,000 acres now available in central Oklahoma. The next year, they rushed for 3.5 million acres of former Cheyenne and Arapaho land to the west. In the Oklahoma land rush of 1893, the 60-mile-wide Cherokee Outlet in the north was opened for settlement, followed by the smallest and final run, in the center of the territory, in 1895.

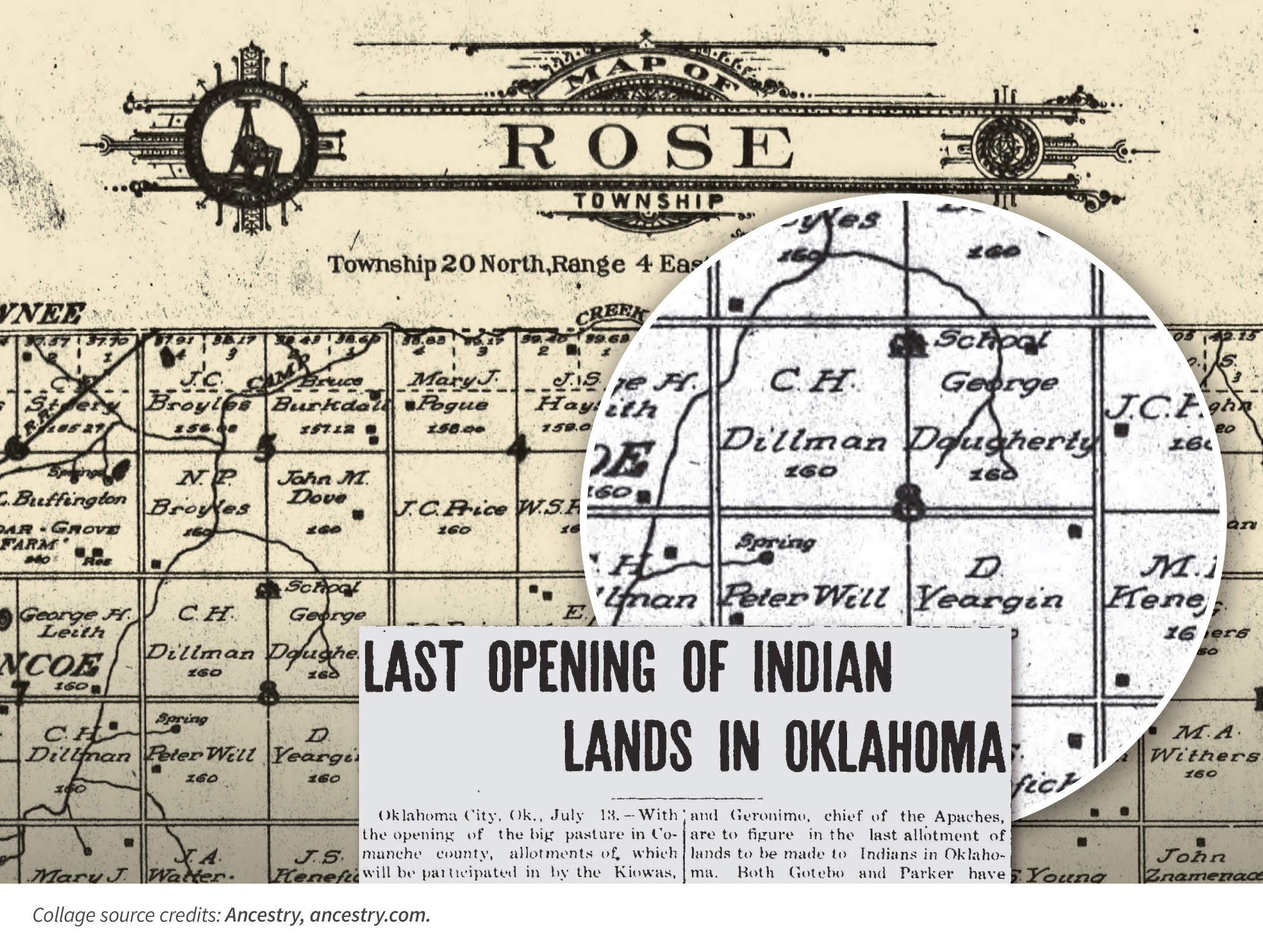

In 1901, President William McKinley ended the chaotic land rushes and proclaimed that the Kiowa-Comanche-Apache and Wichita-Caddo reservations would be sold by lottery, thereby violating long-standing tribal treaties. About 165,000 people registered for 13,000 homesteads and hoped their number would be called on August 6. Winners were given a specific plot of land; Sooners had no advantage.

The government changed tack again in 1906, when it opened the Big Pasture—a 480,000-acre area on the Red River in the south—by auction. Over 7,000 people bid for 3,000 160-acre plots, making their offer in sealed envelopes submitted to land officers.

As the number of settlers grew, they began pushing for statehood to gain representation in Congress. In an attempt to stave off settler encroachment, Native representatives from across Indian Territory convened in 1905 to produce a state constitution and proposed a state of their own: Sequoyah. However, in 1907, President Theodore Roosevelt admitted Oklahoma alone as the country's 46th state, merging Oklahoma Territory and Indian Territory into one unit.

Where Can I Find Early Oklahoma Records?

Many historical collections on Ancestry offer hints about your family's potential involvement in the early days of Oklahoma’s history. Vital records and federal censuses can show if your ancestors were born or married in Oklahoma, or if they ever lived there. You may also find accounts about life in Oklahoma—before it became a state—in the Oklahoma and Indian Territory, Indian and Pioneer Historical Collection, which include transcripts of oral histories from the formerly enslaved, among others. Here are a few additional places to start your search.

Land Records and Land Ownership Maps

General U.S. land records, as well as the 72 tract books in the Ancestry Oklahoma Land Run and other Land Records (1889-1926) can tell you where people owned property. You may also explore records related to land the government distributed to Native Americans. The Land Allotment Sales records include the name, age, and tribal nation of people who sold their property.

Explore the Land Ownership Maps, 1860-1917 on Ancestry®. Filter for Oklahoma to browse records from that area, which date from 1906 to 1912 and are listed by county. Kingfisher, Oklahoma, and Payne Counties were part of the land that was up for sale in 1889, so if your ancestors owned land there, they may have participated in the first land rush.

Oklahoma and Indian Territory Census Records

When Oklahoma became a U.S. territory in 1890, the government conducted a census. The Oklahoma Territorial Census includes each person's name, age, and birthplace, as well as how many years they had lived in the U.S. If your non-Native ancestor lived in Oklahoma in 1890, there's a good chance they participated in the 1889 land rush. There was another census just before it became a state, but only records from Seminole County survive.

The 1890 Oklahoma census is especially valuable because most of the 1890 U.S. Census was destroyed in a fire. The Oklahoma Territorial Census is one of the few such records from that time.

If you have Native American or Freedman heritage, search for your ancestors in the Indian Census Rolls for Indian Territory and Oklahoma Territory, which span 1851 to 1959. These records typically include name, age, tribe, and reservation, and some records also include the name of an ancestor/former slaveholder or the former slaveholder of a person’s parents. Other collections to review include Native American Citizens and Freedmen of Five Civilized Tribes (1895-1914) and the Wallace Roll of Cherokee Freedmen (1890-1893).

Oklahoma Marriage Records

Marriage records for this area include Native Americans, Blacks, and white settlers. Explore the Oklahoma and Indian Territory Marriage, Citizenship and Census Records, 1841-1927, and Select Marriages, 1870-1930. These collections may tell you if your ancestors were in Oklahoma around the time of the land rushes.

Historic Photos of Oklahoma

Ancestry® has almost 800 images of Native Americans in Oklahoma, dating from 1850 to 1950. While few individuals are identified, images usually include the name of a tribe or a short caption, so you can search keywords like "Cherokee" or "Comanche." (As with all collections of historical photos, this one contains sensitive images of and references to deceased Indigenous people.)

The Ancestry® Library of Congress collection has more than 500 images of the area around the turn of the century. You can search for a specific location, like Tullahassee or Guthrie, or filter for Oklahoma to see what’s available.

Do you have Oklahoma roots in your family tree? Join Ancestry® to explore extensive record collections and discover your relatives’ history. Start a free trial today.

References

"All-Black Towns." Oklahoma Historical Society. Accessed July 31, 2022. https://www.okhistory.org/publications/enc/entry.php?entry=AL009. Ashcraft, Jenny.

"Boomers and Sooners: The Oklahoma Land Rush of 1889." FishWrap: The official blog of Newspapers.com, September 11, 2020. https://blog.newspapers.com/boomers-and-sooners-the-oklahoma-land-rush-of-1889/.

"Big Pasture." Oklahoma Historical Society. Accessed July 31, 2022. https://www.okhistory.org/publications/enc/entry.php?entry=BI003. Bradsher, Greg.

"How the West Was Settled." National Archives and Records Administration, 2012. https://www.archives.gov/files/publications/prologue/2012/winter/homestead.pdf.

"Cheyenne-Arapaho Opening." Oklahoma Historical Society. Accessed July 31, 2022. https://www.okhistory.org/publications/enc/entry.php?entry=CH031.

"Dawes Act (1887)." National Archives and Records Administration. Accessed July 31, 2022. https://www.archives.gov/milestone-documents/dawes-act.

"Dawes General Allotment Act." Encyclopædia Britannica. Accessed July 31, 2022. https://www.britannica.com/topic/Dawes-General-Allotment-Act.

"The Great Land Run." Guthrie News Leader, April 7, 2021. https://www.guthrienewsleader.net/index.php/news/great-land-run. Harmon, Maya.

"Blood Quantum and the White Gatekeeping of Native American Identity." California Law Review, April 2021. https://www.californialawreview.org/blood-quantum-and-the-white-gatekeeping-of-native-american-identity/.

"The Homestead Act of 1862." National Archives and Records Administration. Accessed July 31, 2022. https://www.archives.gov/education/lessons/homestead-act#.

"Indian Removal Act: Primary Documents in American History." Library of Congress. Accessed July 31, 2022. https://guides.loc.gov/indian-removal-act.

"Kiowa-Comanche-Apache Opening." Oklahoma Historical Society. Accessed July 31, 2022. https://www.okhistory.org/publications/enc/entry.php?entry=KI020.

"Kiowa." Oklahoma Historical Society. Accessed September 23, 2022. https://www.okhistory.org/publications/enc/entry.php?entry=KI017.

"Land Run of 1889." Oklahoma Historical Society. Accessed July 31, 2022. https://www.okhistory.org/publications/enc/entry.php?entry=LA014.

"Native Americans and the Homestead Act." National Parks Service, November 29, 2021. https://www.nps.gov/home/learn/historyculture/native-americans-and-the-homestead-act.htm. Official General Land Office Story Map.

"Public Lands, Homesteading, and Memorial Day." ArcGIS StoryMaps, May 16, 2021. https://storymaps.arcgis.com/stories/d2583c870c554962b42e469a1ae1d09a.

"The Oklahoma Land Rush Begins." History.com, November 16, 2009. https://www.history.com/this-day-in-history/the-oklahoma-land-rush-begins.

"The Pacific Railway Act of 1862." United States Senate. Accessed September 23, 2022. https://www.senate.gov/artandhistory/history/common/generic/PacificRailwayActof1862.htm.

"Proclamation 288—Opening to Settlement Certain Lands in the Indian Territory." The American Presidency Project. U.C. Santa Barbara, March 23, 1889. https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/documents/proclamation-288-opening-settlement-certain-lands-the-indian-territory.

"Proclamation 460—Opening of Wichita, Comanche, Kiowa, and Apache Indian Lands in Oklahoma." The American Presidency Project. U.C. Santa Barbara, July 4, 1901. https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/documents/proclamation-460-opening-wichita-comanche-kiowa-and-apache-indian-lands-oklahoma.

"Rushes to Statehood: The Oklahoma Land Runs." National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum. Accessed July 31, 2022. https://nationalcowboymuseum.org/explore/rushes-statehood-oklahoma-land-runs/.

"Sac and Fox Opening." Oklahoma Historical Society. Accessed July 31, 2022. https://www.okhistory.org/publications/enc/entry.php?entry=SA002.

"Saracen." Quapaw Nation. Accessed September 23, 2022. https://www.quapawtribe.com/598/Saracen.

"Sequoyah Convention." Oklahoma Historical Society. Accessed July 31, 2022. https://www.okhistory.org/publications/enc/entry.php?entry=SE021.

"Settlement of the Southern Plains." National Parks Service, April 10, 2005. https://www.nps.gov/jeff/planyourvisit/settlement-of-the-southern-plains.htm.

"State Area Measurements and Internal Point Coordinates." U.S. Census Bureau, 2010. https://www.census.gov/geographies/reference-files/2010/geo/state-area.html.

"Statehood Movement ." Oklahoma Historical Society. Accessed July 31, 2022. https://www.okhistory.org/publications/enc/entry.php?entry=ST025.

Top photo collage: Land Office, Oklahoma. Library of Congress. https://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2014682280/resource/. Indian head. Oklahoma and Indian Territory, U.S., Indian Photos, 1850-1930. Ancestry.com. https://www.ancestry.com/discoveryui-content/view/140:60556?_phsrc=WsL7&_phstart=successSource&ml_rpos=2&queryId=9087e268cb6a32ff9e1de2ee4ef8cae5. Plot map. U.S., Indexed County Land Ownership Maps, 1860-1918. Ancestry.com https://www.ancestry.com/discoveryui-content/view/179271:1127?_phsrc=WsL8&_phstart=successSource&ml_rpos=3&queryId=f505b836241de6a5ede4b702a7809713.

Bottom photo collage: Newspaper headline. Ancestry.com. https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/6531/images/NEWS-OK-TH_EV_NE.1906_07_13_0004?ssrc=&backlabel=Return&queryId=5d3fc3196fcf82182e6c361ba1757e5e&pId=475247620&rcstate=NEWS-OK-TH_EV_NE.1906_07_13_0004%3A2113%2C3000%2C2174%2C3038%3B2195%2C3000%2C2338%2C3038%3B1725%2C3713%2C1784%2C3750%3B2773%2C4425%2C2833%2C4462. Plot map. U.S., Indexed County Land Ownership Maps, 1860-1918. Ancestry.com. https://www.ancestry.com/discoveryui-content/view/179271:1127?_phsrc=WsL8&_phstart=successSource&ml_rpos=3&queryId=f505b836241de6a5ede4b702a7809713.