Ancestry® Family History

Naturalization Records

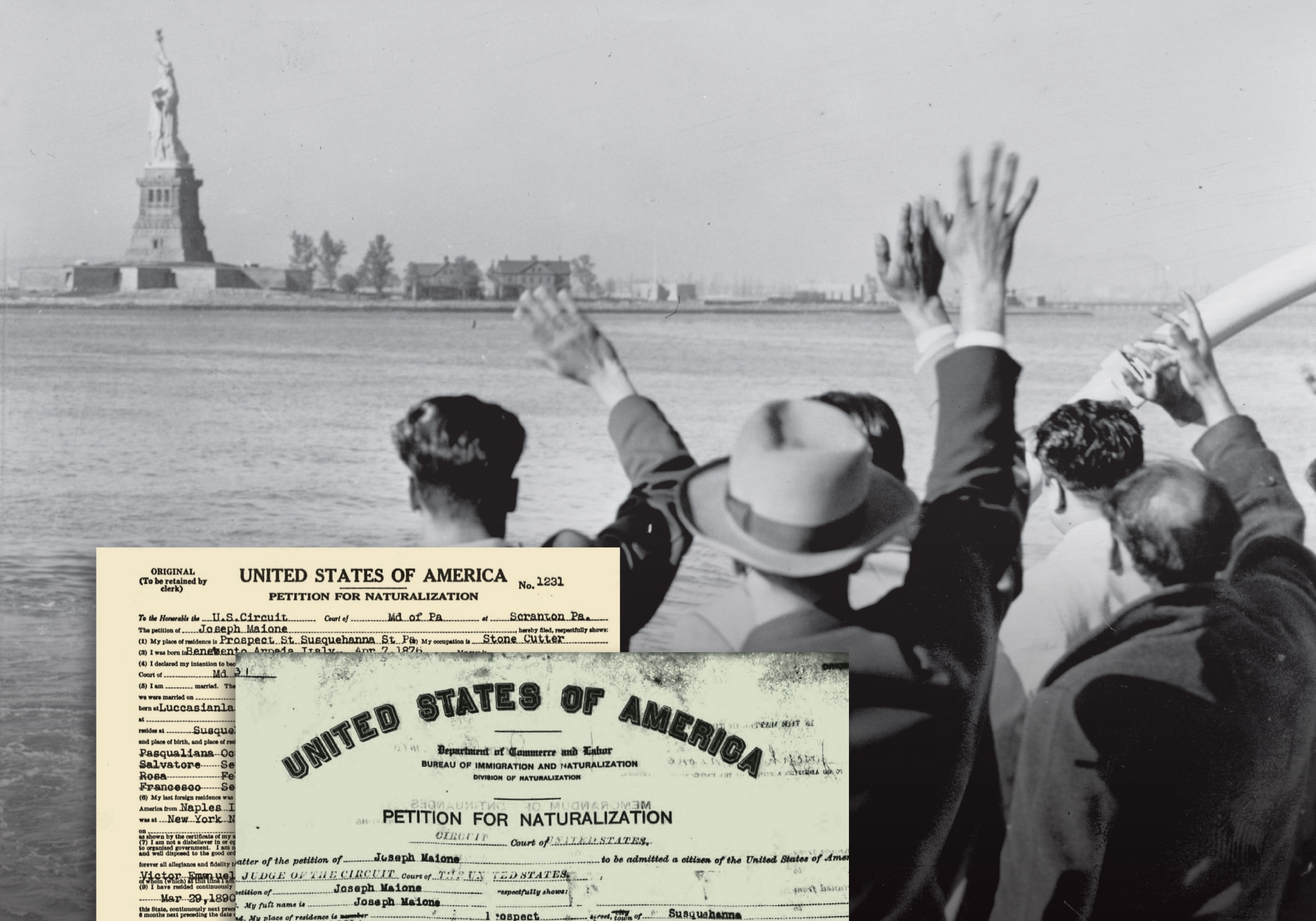

Naturalization records document the path to citizenship for immigrants to a new country. In the U.S. this process goes through our court system. These records can be valuable sources of information as you explore your family history. The exact details you’ll find can vary depending on the court to which the records were submitted and the year in which the records were created.

Before 1906, a variety of forms or handwritten documents were used, so you’ll sometimes find varying degrees of information. After 1906, when the naturalization process was turned over to the Bureau of Immigration and Naturalization (now the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services, or USCIS), most naturalizations were formalized in federal courts—though there were some exceptions. These post-1906 records are more detailed than those created earlier and can be very rich in information.

Naturalization Records You’ll Find on Ancestry®

The process of naturalization was typically a multi-step process, requiring the filing of multiple documents. Here are some of the naturalization records you’ll find on Ancestry®—and the details they could reveal about your family members.

Declarations of Intent

An immigrant could submit their "declaration of intention" (also known as "first papers") typically two years after arrival in the U.S., depending on the laws at the time.

The earliest declarations were sometimes entirely hand-written, but pre-printed forms came into use relatively early. They included the applicant’s name, the date of the declaration, how many years in the U.S. (and sometimes residency in the state as well), where the applicant was from (typically just the country, although there are exceptions), a witness attesting to the immigrant’s good character, and an oath of allegiance. Occasionally an occupation and/or arrival details would also be included.

Post-1906 declarations of intention can include much greater detail including:

- full name

- residence

- occupation

- physical description

- date and place of birth (down to the town name)

- names of immediate family members (wife, children, and in cases where they derived citizenship from their father, his name and birthplace)

- if married, when and where they were married and the spouse’s birth date and place and residence

- last foreign residence

- emigration port and port of arrival

- date of arrival and ship name

Beginning July 1, 1929, declarations of intent and naturalization certificates may also include a photograph of the petitioner.

Petitions for Naturalization

The petition for naturalization was the next step in the naturalization process. It had to be submitted to the court who had filed a declaration of intention unless it was waived by military service). And petitioners were typically required to meet a five-year* residency naturalization requirement.

These records are sometimes known as "second papers" or "final papers." As with the declaration of intention, earlier petitions tend to be leaner in detail than those filed in later years, but there are exceptions. Post-1906 petitions will include many of the same details as you’ll find in post-1906 declarations, with the addition of the names of witnesses (typically friends, neighbors, or other associates of the immigrant), who are vouching for the residency requirement.

Certificates of Arrival

Beginning on June 29, 1906, certificates of arrival were issued to prove a non-naturalized immigrant had met residency requirements. When an applicant filed a declaration of intent, the name of the ship and date and port of arrival were given. That information was verified in passenger lists from that port and a certificate of arrival was issued to be filed with citizenship papers. For people researching their family history, these records tend to be a bit less common than the petitions for naturalization and declarations of intent.

Certificate of Naturalization or "Stubs"

Typically the certificate of naturalization was kept by the newly naturalized citizen, but sometimes a copy was kept by the court. In other cases, the certificate was torn from a book, and a stub with some of the basic information was retained by the court.

Tips for Learning About Immigrant Ancestors through Naturalization Records

Don’t limit your naturalization records search to one city or state. Before 1906, naturalizations could take place in any court of record, so naturalization records can be found on the local, state, or federal level. You may even find them in criminal or marine courts. Sometimes the immigrant may have filed a declaration of intention in one court, possibly near their port of entry, and completed the process in an entirely different location; so the declaration of intention may be in one place and the petition in another. Because of the sometimes scattered location of these records, the digitization of these records in collections like those on Ancestry allow you to search records from multiple courts in one place.

Census records can be helpful in your research of your family immigration stories by narrowing the window of the naturalization date. U.S. census records for the years 1900 through 1930 include naturalization status of immigrants and the 1920 Census also asked for the year of naturalization. For those immigrants who had not begun the naturalization process, their status was noted as "AL" (alien). Immigrants who had declared their intention to naturalize were noted as "PA" (papers applied). And those who had completed the process were listed as "NA" (naturalized). In addition, the 1870 U.S. Federal Census had a column to be checked for "Male citizens of the U.S. aged 21 years and upwards." Non-native-born males who checked this column would have been naturalized prior to 1870.

Remember that not all immigrants naturalized, and not all who started the path to citizenship completed the process. The reason for naturalization may have been for the right to vote in elections or patriotism. In times where certain ethnic groups were being targeted (e.g., Germans during the world wars), they may have naturalized to show their allegiance. Some naturalized because of state law. Sometimes you had to be a citizen to be licensed occupationally in some way or to hold public office. In Illinois in 1826, you had to be a citizen to be eligible to serve in a command position in the militia. In New York, until 1825, immigrants needed to naturalize to purchase, own, sell, or bequeath real property. Legislation passed that year that allowed non-naturalized immigrants to file a deposition of intent stating they intended to become a citizen so that they could overcome that hurdle.

You may be able to find more (or less) information about certain immigrant ancestors, depending on their gender and age at the time of naturalization. From 1790 to 1922, the wives and minor children of naturalized men derived citizenship from their husband or father, respectively. This also meant that an alien woman who married a U.S. citizen or an immigrant who naturalized automatically became a citizen at the time of her marriage or her husband’s naturalization. From 1790 to 1940, children under the age of 21 automatically became naturalized citizens upon the naturalization of their father. Unfortunately, however, names and biographical information about wives and children are rarely included in declarations or petitions filed before September 1906.

The naturalization status of women could be less straightforward than that of men, as laws changed. In 1907 the law changed for women, and if a woman married a non-naturalized immigrant after that date, she lost her citizenship. If her husband naturalized, she still derived her citizenship from him, and in this way could regain her citizenship. The 1922 Cable Act, sometimes referred to as the Married Women’s Act, established every woman’s citizenship based on her own eligibility, separate from her husband’s status.

Naturalization records can be a great resource for those researching immigrant ancestors who changed their names after immigration. In some cases, immigrants changed their names in order to assimilate or to find work during times when certain immigrant groups faced discrimination. But because passenger lists were used at times to verify residency, an immigrant who had changed their name would have wanted to include the name they arrived with in the U.S. in their naturalization records.

Your Family's Naturalization Story

Your immigrant ancestor's naturalization record can lead you to many more records, such as passenger lists, census records, and vital records. And it could lead to details not just about the ancestors filing for citizenship but also information about their children, like their birth dates and places of birth.

More than that, naturalization records are part of your family story, representing a deepening of the family roots in America for the immigrants and their descendants. Search for your family naturalization stories on Ancestry today.

*The residency requirement was increased from 5 years to 14 years for a short time beginning in 1798 and ending in 1802.

References

"History of the Declaration of Intention (1795-1956)." USCIS, January 6, 2020. https://www.uscis.gov/about-us/our-history/history-office-and-library/featured-stories-from-the-uscis-history-office-and-library/history-of-the-declaration-of-intention-1795-1956.

Laws Passed by the Fourth General Assembly of the State of Illinois, at Their Second Session, Commenced at Vandalia, January 2, 1826, and Ended January 28, 1826. Blackwell: Printer to the State, 1826.

"New York Naturalization and Citizenship." FamilySearch Wiki. Accessed January 19, 2021. https://www.familysearch.org/wiki/en/New_York_Naturalization_and_Citizenship.

"New York, U.S., Alien Depositions of Intent to Become U.S. Citizens, 1825-1871." Ancestry®. Accessed January 19, 2021. https://www.ancestry.com/search/collections/5355/.

Szucs, Loretto Dennis. They Became Americans: Finding Naturalization Records and Ethnic Origins. Lehi, UT: Ancestry Inc., 1998.